Sesquicentennial Anti-Rent Article (Knox)

From the booklet, Knox, New York Sesquicentennial, 1822-1972, Mrs. Frieda Saddlemire, Chairperson - Used with permission from the Knox Historical Society

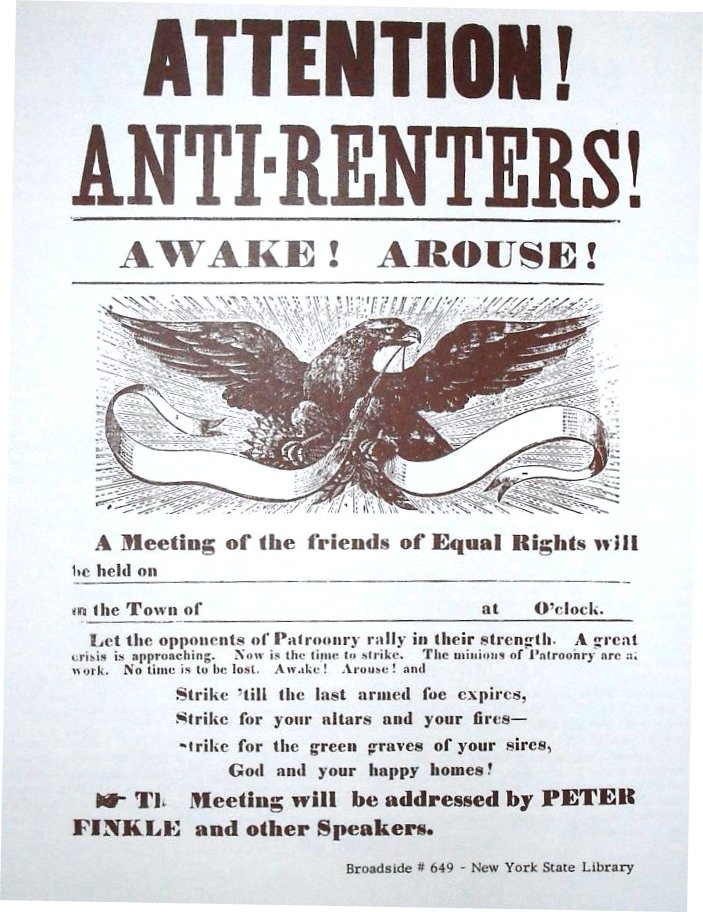

ANTI-RENT WARS

Stephen Van Rensselaer III, admirers had good reason to call him the “Good Patroon,” because he had let nearly half a million dollars in rent go uncollected, died in 1839. Upon his death, the West Manor (mainly Albany County) was inherited by his son, Stephen IV, who ordered that all delinquent rents be collected forthwith and threatened actions to recover the farms of those who did not pay up at once.

The young patroon's ultimatum weighed heavily on many tenants; the farms which they, and their fathers before them, had hacked and grubbed out of the harsh wilderness were now threatened with abrupt seizure. Resentment against the patroon system had long smouldered among the tenants of the manor, especially among the farmers of the hill townships of Berne, Westerlo, Rensselaerville, and Knox. The old patroon had been mindful of the latent hostility, and it is said that he never ventured into the Helderbergs without an escort of armed outriders. He was careful, too, to take no action that would unite the tenants against him. Now, however, the young heir's ultimatum achieved that unity of opposition, and the resentment in the hill townships flared like a grass fire in the wind.

Men gathered in angry groups to discuss the ultimatum and to renew the old, rankling discontents: the perpetual rents, their status as tenants from which there was no possibility of escape. the “incomplete sale” contracts which would never culminate in ownership of the lands they worked. Farmers for whom the rents were no hardship joined with those for whom payment was impossible, and together they confronted the patroon with a united opposition — a common defiance.

Stephen's agents fanned out through the hill townships to collect the rents, but they returned, for the most part, empty-handed. Stephen then ordered the farmers to form a committee and to meet with him. The tenants complied, but when the committee went to the manor, Van Rensselaer refused to speak with them. He stalked through the room in stony silence while his agent demanded of the tenants that they submit their grievances in writing in the form of a petition. The farmer-delegates were disappointed. They were working farmers, not petition writers, and they had hoped to discuss their problems with the patroon on a man-to-man basis, just as they threshed out their individual problems over stone walls, in church yards, and over the wheels of wagons. But, once again, they complied.

A week later the patroon's response was delivered by his agents. Stephen acknowledged that he was prepared to modify the policies of the manor in some respects, but he insisted that the basic issue — back rents — must be resolved by full payment before other matters were discussed. The back rents, he said, were the concern solely of the individual debtor and the estate. That issue, he said, was “a matter with which you have nothing to do.” The writs of ejectment followed, and the Anti-Rent War began.

The Helderberg War

Oh hark! in the mountains I hear a great roar;

Those Helderberg farmers are at it once more.

With their war whoops and Indians most wickedly bent

On shaving Van Rensselaer out of his rent:

And the way they make war

Is to feather and tar

Every unfortunate law-seeking gent

Who by landlord or sheriff among them is sent..."

— From the Workingman's Advocate

The hill farmers responded with a document addressed to the “pretended proprietors” of their soil. This new Declaration of Independence included the vow, “We will take up the ball of the Revolution where our fathers stopped it and roll it to the final consummation of freedom and independence...”

Stephen's agents, sheriff and deputies rode through the hills with their writs. But wherever they went, tin horns and conch shells signaled their arrival, and they found the roads blocked by the calico “Indians”, silent farmers, armed and mounted, who galloped out of the woods whenever the horns sounded in the hills.

Finally, in 1852, after years of violence, Stephen IV abandoned his attempt to subdue the rebellious tenants of the hill townships, and he offered the West Manor to land speculators. The leases in the Helderbergs were bought up by Walter S. Church, who was determined to crush the hill town rebels once and for all in order to reap the anticipated profits of his investment. Church placed the subjection of the Town of Knox high on his list of priorities. Arthur B. Gregg, author of Old Hellebergh describes the reason for Church's concern: Many bitter anti-renters of that township, descendants of pioneer Connecticut yankees, had ignored every demand for delinquent rents and vigorously opposed attempts to dispossess.

With the sheriff and the military courts as the instruments of his policy, Church moved against Knox. In 1866, a military force moved to Altamont by train and then marched up the hill to encamp at the intersection of the roads leading to Warners Lake and Thompsons Lake, now Routes 157 and 157A. There they stayed from July until October.

In Old Hellebergh, a pertinent report by Senator Colvin to the Landholders Convention is cited:

“The military have held possession of the Helderberg towns. Dwelling houses have been broken into, furniture cast out upon the public highway. The military have occupied the roads. People have been stopped while peaceably traveling on business, their vehicles searched and then ordered to move on. Men looking on at a distance were fired on, chased and had to fly to save their lives. Sheep were killed, hen roosts broken into and robbed, grain taken, fed and destroyed, potato fields dug, corn gathered, eaten and wasted, garden vegetables, flowers rooted up wantonly. Firewood, carefully collected for the winter was burned and fences and buildings afterward. While men made days and nights hideous with drunken revelry.”

Col. Church's counsel, Judge Rosendale, gives this version of the incident.

In July 1866 a military expedition was sent to the town of Knox to serve process which was met by a body of resisters who fled, however, on approach of the soldiers. Nine persons were arrested and sent to Albany Police Court. As late as September, 1866, two companies of local militia were sent to the anti-rent district, where tenants had committed excesses upon persons holding property of tenants ejected for non-payment of rent: the militia brought fourteen prisoners accused of resisting the Sheriff's officers.

In 1866, according to the report of the Landholders Convention, as cited in Old Hellebergh:

the sheriff, Col. Church and an armed gang went to the premises of Amos and Mathias Warner (now the Kendall home) without a process and broke into his house and began to throw property out upon the public road. An Irishman. a blacksmith, living in the neighborhood came in, witnessed the devastation and objected to the removal, closing and holding the door. This was claimed as resistance. Col. Church returned to the city, called out the military and marched them to the house of the Warners, took the possession of the farm, encamped there picketing the highways. The property was seized and appropriated and never did the Sheriff let go his hold until the Warners agreed to pay the extortionate sum of $4,000.

The property of the Rev. Mr. Daniels, pastor of the Lutheran Church in the neighborhood(this church was located where Robert Rock now lives) and who had rented from the Warners a part of the dwelling house, shared the same fate as the Warners property. It, with his library of fine and handsomely bound books was also cast upon the public highway in the very midst of a pelting rain storm.

Similar scenes were enacted in the same neighborhood against the mother of Palmer Gallup who was never sued, and against Conrad Bather and Son (north of the barn on the property now owned by Frank Rocker). Complaints were also made against Hanes, Gallup and others, they were arrested and treated in the most ruffianly and brutal manner. Their dwelling houses were broken into, in the night by armed men and they were handcuffed and refused either food or drink for the term of a whole day. One of the farmers, a most quiet man. Mr. Hiriam Hane assures me, was dragged from his dwelling house in the night time, only himself and old mother being home, handcuffed and kept in that condition without food or drink for ten hours and although he begged piteously for a glass of water it was refused him and it was not until he was lodged in police office that his burning thirst was relieved by a member of the police department.

Today a historical marker in front of the home of Frederick Kendall on Warners Lake Road, Route 157A, proclaims the fact that this was the scene of the anti-rent eviction described in the report of the Landholders Convention.

Old Hellebergh records Elias Warner's first-hand description of the troubled period.

"There were stirring times," said Mr. Warner. "The nights were made hideous by the Anti-renters riding by on horseback and blowing horns. Anyone who paid his rent was hated, and they would cut the tails off the horses belonging to such people." This recalls Henry Christman's account, in the Acknowledgements section of Tin Horns and Calico, of an interview with William Quay, described as "the last of the Anti-Renters." Quay, who had been arrested in 1865 during Church's last foray into the Helderbergs, told Mr. Christman of "the Hell we raised on the mountain."

Old Hellebergh cites a report of the Albany County Supervisors for 1866, showing a bill for $1,295.52 for supplies for Col. Church and others to "subdue the late Unholy Anti-Rent War."

Mr. Gregg further states, “The days of the Calico Indian, tar and feathers, night riders and council shells are gone. No more are court calendars crowded with land cases but if you buy property or accept a mortgage in the territory of old Rensselaerwyck, it is well to have a complete and thorough search.”