Berne Carding and Fulling Mills

Early carding and fulling mills in Berne

The Miner Walden Carding and Fulling Mill was built shortly after 1797. It was also used to produce wooden shoe pegs before becoming part of Simmons Axe Factory in 1825. This mill had its own dam, a log structure with stone wing walls. As a grist mill many years later, it used a horizontal tub mill or turbine for power with the tailrace existing out the bottom of the structure. In 1825 it may have had an outside overshot wheel, with the tailrace high enough to use the spent water for additional wheels downstream.

In the 1830's a carding and fulling mill was built by Malachi Whipple along with William Ball and Lyman Dwight. (See Whipple, Ball, Dwight Mill.)

Source:Our Heritage article by Robert Lambert

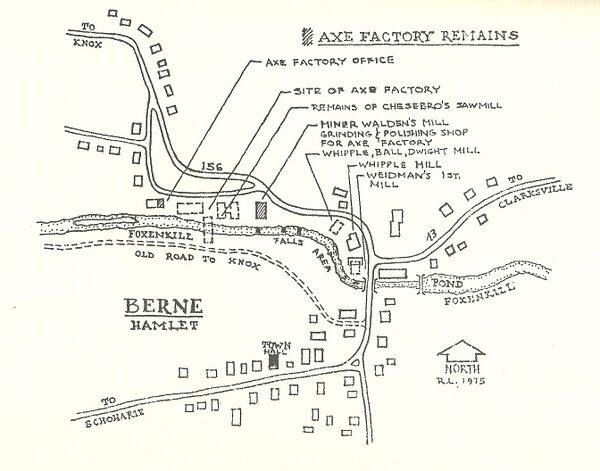

1975 map by Robert Lambert, from Our Heritage

Carding

Before wool can be spun into yarn for knitting or weaving into cloth, it first must be brushed, or carded. This tedious task was successfully mechanized in the second half of the 18th century by several British inventors, principally Richard Arkwright and James Hargreaves. By the late 1780s carding machines began to be built in the United States, carding as much wool in minutes as a hand-carder could do in as many hours. By 1811 the federal government estimated that on average every town had at least one carding mill where farm families could bring their wool and pay to have it carded. This made the domestic production of cloth much easier by removing this time-consuming step.

Since 1773, carding machines have had the same basic design as they do today. They consist of a series of round brushes that align wool fibers as the wool passes from one end of the machine to the other. Each cylinder is covered with bent iron wires, which grab wool in one direction and release it in another. Carding mill machine (back view)

Clean but tangled wool is fed into the machine from a conveyor belt, called a feed apron. Two small cylinders--called licker-ins—transfer the wool from the apron to the tumbler, which deposits it on the large main cylinder. This cylinder carries the wool through the machine. Along the way, it is removed by workers. Strippers then take it from the workers and deposit it back on the main cylinder. Near the end of the machine, a fancy with long bristles fluffs the wool up on the main cylinder so that a doffer can remove it. The wool is rolled up into rolls or silvers for spinning as it passes between a fluted cylinder and a concave shell. [1]

Fulling

The word “fulling” is derived from “furling” meaning to contract and is a process of shrinking homespun woven cloth, either wool, cotton or linen. For centuries, yarn was spun and woven at home. It was not comely to wear until the loose “web” had been fulled, washed, dyed and tended (spread to shrink and dry). In fulling the cloth is subject to moisture and heat, agitation or friction of some kind, such as rubbing or beating, and a cleaning and lubricating agent. In fulling the fibers move more freely and work themselves loose from the spun thread and become entangled in one another, thus filling in the spaces between the warp and weft and creating a fuzzy pile-like layer on the surface of the weave.

A fulling mill generally consisted of heavy wooden mallets which were mechanically made to continually rise and fall on the cloth in a water-filled trough. The device was fun by a waterwheel. The loosely woven cloth was placed in the fulling trough, together with hot water and some form of detergent. Then the water wheel began to turn, tappet arms lifted heavy wooden pestles or mallets alternately and then released them so that they struck the under part of the heap of cloth. The upper part of the heap then fell over and during the fulling operation the position of the cloth changed continuously under the pounding of the mallets.

In Dobson’s Dictionary of Art, Science and Miscellaneous Literature in 1798, cloth was “laid in urine, then in fuller’s earth, and water and lastly in soap dissolved in hot water. Soap alone would do very well, but this is expensive . . .” The chief scouring agent was stale urine; the nitrogen content of urine was responsible for its detergent qualities. “Fermented” urine was quite a handy and useful liquid, being used both in the fulling and in the dyeing, according to a 1816 book entitled, The Dyer’s Companion. Up to 1800 there was a tub or two or urine in every house. After 1800 the use of urine as a detergent was slowly replaced by fuller’s earth, which resembled clay, and soda and soap to remove grease dirt and oil found in the wool during carding.

The cloth was periodically removed and repositioned for even fulling. The cloth could then be dyed. By increasing the density of the cloth, the weight per yard was increased and it had more resistance to wear and to weather. There were bins in the fulling mill to keep the batches of cloth separated from each other. After being fulled and dyed, the cloth was suspended in open fields for stretching, so that it would dry evenly and square. Fulling mills were located in open country with plenty of field space upon which the tenter frames could e set up and fabric dried in the sun and air. The cloth then passed through a furler who removed knots, rough spots and loose threads. The cloth was napped by teasels, or fuller’s thistles which raised a fine nap and resulted in a material that felt softer. It was then sheared by the shearman so that the surface was even. Teasels, a tall herbaceous biennial plant, were not planted in this country until 1833, before which they were imported from Europe. The fulling operation took from 48 to 65 hours.[2]

Sources